Creating Visuals with Gemini 3

Introduction

In this post, I am going to illustrate, and share my thoughts about, how to create visuals for learning with Google’s Gemini 3. This is inspired by a Google Deepmind’s YouTube video that turns a research paper into an interactive website:

This is the prompt used in the video (see below):

I want to learn about the [CONCEPT]. Create beautiful, elegant 3D interactive visuals that explain it. The app should be in light mode, with great graphic design. It should be a single block of code that I can open in [BROWSER].

Replacing the placeholder [CONCEPT] with a concept you are interested in learning, and [BROWSER] with name of a browser you prefer.

As we would like to see the canvas with our smartphone, and often we would like to understand a concept via interaction, this is the updated version of the prompt:

I want to learn about the [CONCEPT]. Create beautiful, elegant 3D interactive visuals that explain it. The app should be in light mode, with great graphic design. It should be a single block of code that I can open in [BROWSER]. Make sure it’s mobile browser friendly, and at the end of it I can get a taste of what it is.

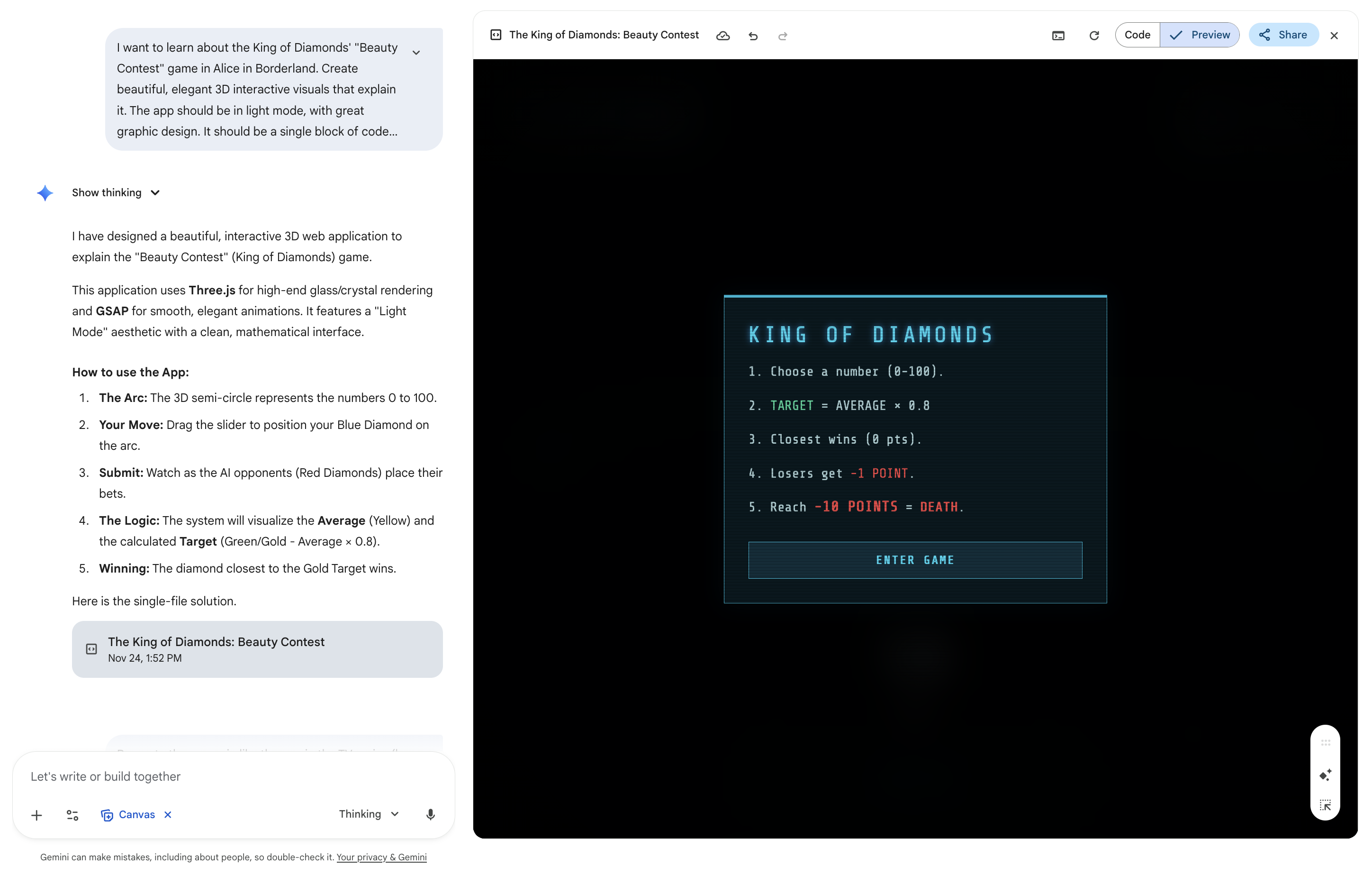

Examples

Here are a few great examples I’ve created recently.

Game Theory

Psychology

Philosophy and Ethics

Discussion

As you try some of the examples above, you realise some similarities:

They are interactive, meaning that a user (or a learner) can play around, and get a sense of what really means

Most visuals illustrate mentally complex concepts. For instance, most examples under Psychology are related to ‘Psychology of Illusion’ - where one might often conclude differently based on personal perceptions.

I think this feature offers valuable opportunities for educators to students in the following scenarios:

Turning mentally abstract concepts into visual: Like mathematics (Nash Bargaining Solution), psychology (virtual bargaining) and arts (Van Vogh), physics (how does light deflect), biology (how does our eye work), philosophy? (The sky is the limit)

Great for perspective taking (or putting oneself into other’s shoes): understanding how duck and hare can be perceived, how dylxesic people read, how colour blinded people view the world

Importantly, these abstract concepts can often be interpreted differently, implying that what Gemini illustrated visually offers one perspective.

With that said, when to introduce these visuals (before or after introducing a mentally abstract concept) matters. If students were introduced these visuals before they imagine how a concept should look like, these visuals offer ‘an anchor’ of how such concept should look like. Take the Schelling’s Model of Segregation as an interactive simulation visual link as an example. It provides message boxes as an interactive guide that faciliates users to navigate through the concepts step-by-step.

This approach, however, implies that these visuals would replace their imagination and cognitive ability when they learn a concept this way.

If, instead, educators introduce these visuals after introducing a concept (treating these as an aid or thinking ‘scaffold’), students could make great use of their imagination while leveraging benefits that these AI tools offers substantially.

Reference

Misyak, J. B., & Chater, N. (2014). Virtual bargaining: a theory of social decision-making. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1655), 20130487.

Nash, J. F. (1950). The bargaining problem. Econometrica, 18(2), 155-162.

Schelling, T. C. (1969). Models of segregation. The American economic review, 59(2), 488-493.

Social Science

Gerrymandering: link

Model of Segregation (Schelling, 1969): link.